A couple of new expressions entered my lexicon this week after I watched some videos by Daniel Schmachtenberger on the site Rebel Wisdom. Schmactenberger’s (let’s just call him Daniel) series of films that come under the title The War on Sensemaking, should be essential viewing for anyone who wants to make sense of why everyone either seems so certain of their views these days, or otherwise are completely bamboozled by events.

Daniel possesses a very rare combination of qualities: a deeply thoughtful and analytical mind combined unfettered by ideology, combined with the ability to patiently explain his insights to a wide audience. Usually, people with this depth of analytical capability work in think tanks for corporations or governments and can expect to be remunerated according to their worth i.e. megabucks. Daniel’s area of expertise is what might be called the ‘information ecosystem’ – the multi-directional system of information distribution that we all rely on to make sense of the world around us – and how it has been hijacked by those who seek to control our thought processes.

I won’t go in any great depth into what he thinks, and what his methodologies are – I recommend you watch the series of videos for that (links at the bottom). Instead, it’s probably enough to say that he considers the combined power of big tech corporations, using AI (artificial intelligence) and social media, are waging a war against us for our minds. If you use the internet, and in particular social media, there will be algorithms that probably know you better than you yourself do. These algorithms are being weaponised against us, displaying news that is designed to rile us up, targeting us with ads and predicting (with increasingly uncanny accuracy) what our next move will be.

One of the tools being used in this battle is the technique of ‘limbic hijacking’. This is a technique that is used to get your emotional centre to react before your logical mind can get to it. Of course, this has been used as a propaganda tool going back a long way, but never before has it been so easy to use it in such a targeted manner. The technique was first used in a modern way in America at the onset of the First World War. Psychologists on Madison Avenue used the services of Edward Bernays – nephew of Sigmund Freud – to make sure the average American felt sufficiently hostile towards Germans that they would enter into a world war (and thus secure Wall Street investments).

The only problem was that Germans were well-liked in the US, and were considered model immigrants. All that changed when cleverly designed cartoons of a German soldiers bayoneting Belgian babies began to circulate (a trick borrowed from the British, who drew cartoons of Irish soldiers bayoneting babies during the Rebellion of 1641). Within months, the average American was willing to go to war with Germany.

Techniques such as this are target the processes of the human brain. The way it works is that the ability of the rational brain to perform a careful and logical analysis of any new information it is presented with is ‘hijacked’ by a flood of emotional stimulus, usually in the form of fear. The amygdala part of the brain, which is sometimes called the ‘irrational mind’, is evolutionarily hard wired to act fast when it perceives a threat so as to preserve the organism in the face of extreme danger. If it wasn’t for this crucial function, neither you nor I would be sitting here as our ancestors would have been pulled apart by cave bears. But in the case of propaganda, the threat isn’t a predator lurking in a bush, it’s in the form of an emotive trigger that causes something called the HPA (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal) axis to forcefully grab the controls from the neocortex (the ‘rational mind’). The fact that this only takes milliseconds to achieve is ideally suited to digital computers, which also work in milliseconds. One could almost say that we are being programmed, like robots.

If you are motivated by a hunger for power, profits and control, and if you are able to get people to think in a way that maximises your advantage in the world, it stands to reason that you will do so given half a chance. Furthermore, should you have access to an almost limitless supply of money through various central bank money printing exercises and company valuation scams, and you possess the network and infrastructure to implement your plan, well, there’s nothing really standing in your way.

This type of ‘narrative warfare’ can be thought of as an asymmetrical battle for our minds, and the side with the biggest narrative weapons are the ones with the most money, or which owns the means of information dispersal (i.e. Facebook, YouTube, Twitter), comes out on top. Not only will you be able to get some people to think exactly what you want them to think by exploiting and amplifying their innate biases until they become weaponised, you’ll be able to get people wasting time and energy fighting one another on social media platforms and news site comments sections, and perhaps even fighting in the streets if that helps further your aims.

As a digital general in the narrative war, the possibilities are endless with your new robot army. By using the fear trigger, as well as other traditional tools of propaganda, you can get your targets to think and do just as you please. What’s more, most of the combatants don’t even realise they are in a warzone and will call out anyone who says so as a ‘conspiracy nut’. A key tactic they use is to create a narrative smog in which many different versions of reality are available, and it becomes almost impossible to parse the truth in any particular situation. This state of confusion disorients people in the information jungle, making it easy to lead them into traps. The method works particularly well for threats that can’t be independently verified by people because they are invisible: it works equally well for invisible gases, invisible germs and invisible ideologies.

Observers with memories longer than goldfish will recall one of the first instances of a viral internet based operation in 2012 when a California based organisation used internet technology to create a huge panic over an obscure Ugandan warlord called Joseph Kony. Like every other warlord in Africa, Kony – if he even existed – used child soldiers, and this was the liminal hijacking trigger that enabled the campaign to be so successful in ‘raising awareness’. The sheer level of frenzied we-have-to-do-somethingness led to it being debated in the UK parliament and made headlines around the world. I recall a not inconsiderate number of my social media connections urging me to sign petitions and demand action against the evil Kony. And then, all of a sudden, Kony vanished from the internet and became a non-issue.

Since the success of ‘Kony 2012’ numerous other highly emotive flash-in-the-pan internet campaigns have rolled out, enabling the narrative engineers to hone their skills. A whole host of nefarious astroturf organisations have been launched off the back of these campaigns, financed and controlled by, well, whoever has enough money and resources to finance and control them. This is impressive, however they have not yet perfected their dark art.

For example, the UK government recently scored an own goal in this respect when it put out a digital poster urging young people involved in the arts and creative endeavours to give up on their dreams and get office jobs. The poster featured a ballerina named ‘Fatima’ with the line “Fatima’s next job could be in cyber (she just doesn’t know it yet).” While the government might have hoped its condescending message to the proles would be gladly received, most people interpreted it as: abandon all sense of your innate individuality and conform to our soulless machine (or else). Thankfully, the backlash against the poster was so intense, and the memes so cutting, the government was forced to admit it was an ‘error’, thus allowing many more people to see it for what it really was: a crude attempt at manipulation. Presumably, some mid-ranking narrative control flak is now wondering what their next career will be in.

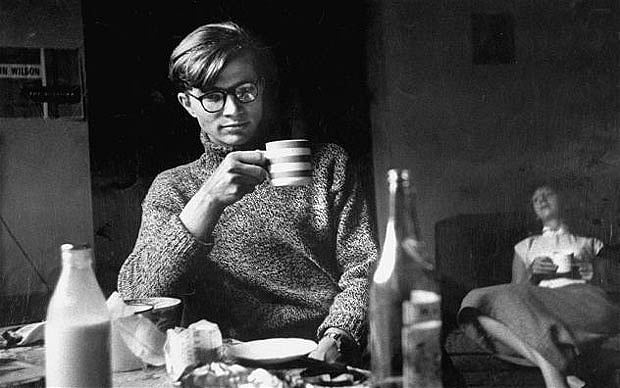

Someone who spent a lifetime developing a practical theory about breaking free from the mind’s tendency to act in an automatic manner was a young English writer from a working-class background, whose first book took the world by storm. Colin Wilson was born and grew up in the English Midlands city of Leicester and moved to London as a young man. As a teenager he found himself working long days in various factories and came to the conclusion that life was so flat, dull and unendurable that it was not even worth living. He had taken to heart T.S. Eliot’s poems The Waste Land and Hollow Men and took the logical decision to opt out of life before it got any more brutal, or, as he put it “give God back his entrance ticket.”

The resolve to kill himself wasn’t a snap decision. Wilson had managed to leave his factory job and get a position in a laboratory, which due to a passion for science appealed to him greatly. But even that proved to be a disappointment, and soon he found himself losing interest in science as well. He escaped into reading literature and found that if he put pen to paper and wrote about his own life it somehow distanced himself from it and provided a greater perspective. Nevertheless, the heavy sense of gloom and meaningless wouldn’t go away, and so he decided to poison himself with hydrocyanic acid. The acid, he knew, would kill him in around 30 seconds, and so he raised the bottle to his lips and prepared to exit his seemingly meaningless existence on Earth. As he did so, a curious thing happened: he split into two Colin Wilsons. One of these Colins appeared to be a teenage idiot with a bottle in his hand, while the other one, standing beside him, was saying “Kill him and you kill me as well – think of how much you’d be losing!” He put the bottle down in shock.

As Wilson writes in his autobiography Dreaming to Some Purpose, “and in that moment I glimpsed the marvellous, immense richness of reality, extending to the distant horizons.” The accompanying feeling of release lasted for several days and set him on a course to write around 150 books over the course of his lifetime, many of which were devoted to understanding how to unlock these experiences at will and set the mind free from its limitations.

Despite his enlightening experience and his new resolve to become an important writer, Wilson remained financially poor. What’s more, he found he had to work continuously in hard jobs just to be able to pay his rent and bills, and this was so exhausting he rarely had the time or energy to write. This was very frustrating to him, as he felt his higher purpose was being held back by mindless work and demanding landladies. Then he hit upon an idea: he would become voluntarily homeless, meaning there would be no rent to pay. And so he got a sleeping bag, told his landlady where to stick it, and went to live like a tramp on Hampstead Heath in north London. He would spend each day writing up his book manuscript in the reading room at the British Museum and then bed down for the night on the Heath in his sleeping bag.

In this unconventional way he managed to finish The Outsider, a study of alienation and genius told through the stories of key thinkers such as Nietzsche, Dostoevsky, Hemingway, Gurdjieff, Hesse and Van Gogh. Wilson’s outsiders were all loners who laboured away on the difficult question of what it meant to be truly alive in a Western culture that had lost its sense of wonder. They worked largely in isolation and often without appreciation.

The book was an instant success, catapulting the penniless 24-year-old into the limelight. Fame and fortune followed as interest grew in the young philosopher and what would be termed his ‘new existentialism’. Unfortunately for Wilson, as an outsider himself, he fell prey to the British gutter press and its incessant attempt to ‘bring down’ anyone whom they considered to have got above the station. He was categorised as an ‘Angry Young Man’ (a group of working-class writers that included Kingsley Amis and John Osborne) and after a few short years in the media’s spotlight he was hounded out of London, thus waving the respectable but fickle literary scene goodbye. Using some of the money from the phenomenal success of The Outsider, he settled with his wife Joy in a cottage in Cornwall, where he lived out the rest of his life.

One of the main contentions that Wilson made in his numerous books was that most people are ruled by an inner ‘robot’. Here, he is referring to the part of the psyche that performs tasks for us in an automatic manner, meaning we don’t have to think about them. An example would be when we are learning to drive a car; at first it is tricky because we have to consciously think about where to put the gearstick or which pedal to press, but then when we become more proficient we don’t have to think about it at all and it becomes second nature. Wilson realised that this ‘inner robot’, whilst useful, also stopped people living meaningful lives if it was given free rein. In fact, there was a danger it would take over our whole lives, leaving us on a kind of permanent autopilot as we drift through life. Because of this, steps were needed to ‘deprogram’ ourselves from relying on the services of our robot all the time. But how?

Based on his own first-hand knowledge, Wilson began to focus on so-called ‘peak experiences’ as a tool for disengaging our autopilot. Theis was a term coined by his friend the American psychologist Abraham Maslow, characterised as experiences where one temporarily goes beyond the normal range of perceptions and sees the world ‘as it is’ – rather than how we are ‘supposed’ to see it – something Wilson had experienced himself when he was about to kill himself. Other writers had reported similar things, including the Russian dissident Fyodor Dostoevsky as he was standing before a firing squad, and English novelist Graham Greene, who used to play Russian roulette in his shed whenever he needed a ‘jolt’ to make him feel alive again.

The key to inducing a powerful peak experience, Wilson surmised, was a sudden threat to one’s comfortable existence. At these moments it is almost as if one splits into two personalities, as he had done, and you are able to see yourself from the outside in the context of the wider world. Such experiences can, of course, be brought on by hallucinogenic drugs, and this is what the Romantic poets had attempted. But this seemed to Wilson to be an unsustainable method as the practitioners had to rely on an external stimulus, and in any case they usually ended up dead before they got old. Instead, Wilson decided to develop methods of attaining peak experiences simply by using the power of the mind, and wondered whether it was possible to induce them more or less continually enabling us to live in a kind of permanent state of nirvana. Even if this were not attainable, one could at least dispel chronic depression and feelings of nihilistic hopelessness if one learned how to, he felt. This search turned out to be the central thrust of his life’s work.

Most of us have had peak experiences, to some extent. Once you have had one, you’re changed permanently, and it becomes possible to spur new experiences simply by recalling past ones. I remember having my first one on a beach in Australia in 1995. I had just recovered from a serious tropical illness which had caused me to lose a third of my bodyweight. I had lain alone in bed for several weeks in a cheap and dirty hotel room in Malaysia. As I lay there, convinced I was going to die, I even wrote self-pitying letters to several people along the lines of ‘this is the last you’ll hear from me’. Luckily, I was rescued by a heavily pregnant Australian woman who busted into my room and sorted me out with a plane ticket to her country so that I could recover. I spent the next month recuperating in Perth and had recovered back to full strength when I took a Greyhound bus to the small town of Exmouth in the northern part of Western Australia.

One evening at sunset, soon after I arrived, I went jogging on the long, sandy and all-but deserted beach. As I paused for breath a surreal scene unfolded before my eyes. By the water’s edge stood a lone Scotsman in full kilted regalia. He was playing a mournful lament on his bagpipes, as if to the sea. I stood there transfixed. The sun touched the horizon as it sank into the Indian Ocean, and the expanse of land and air around me was bathed in a soft yellow light. At the same moment several kangaroos bounded towards me, including a couple of young ones, and – perhaps the oddest part – a small spotty looking shark unaccountably wriggled out of the water onto the wet sand and began to flap around as if it wanted to play a game. As I took in this bizarre scene unfolding around me, I had the sudden sense of everything being connected in the whole cosmos. All the hardship and stress I’d endured over the previous couple of months instantly vanished and it felt almost as if the universe, through the medium of nature, was saying ‘Welcome Back!’.

This incredibly strange experience probably only lasted a few seconds, but just thinking about it now – a quarter of a century later – brings back a faint echo of the feelings I experienced at the time. I feel somehow expanded and there’s a warm feeling that everything is right with the cosmos, despite the day-to-day worries of life. Since then I’ve had several more peak experiences, one of which I detailed in my book The Path to Odin’s Lake.

Colin Wilson described several more peak experiences of his own, some of them seemingly very mundane to the outside observer. One occurred while he was travelling on a train during a wet and gloomy day in southern England, his head full of worries about deadlines and other niggling anxieties. He had a bit of a hangover and hadn’t slept well. Suddenly, and without warning, the world lit up with some kind of invisible radiant light and he was flooded with a feeling of everything being in balance. It felt like a kind of cosmic message of reassurance, he noted, proclaiming “all is well”. He later went on to note, at these times everything is exposed for what it really is: the inner robot shuts down and you become ‘fully awake’. If we are fully awake it becomes harder for propagandists and narrative controllers to gain a purchase on our minds.

It’s because of clues like that that I feel that Wilson’s writings have a lot more to offer us as we struggle to find new meaning in turbulent times. His fictional book The Mind Parasites is a story of psychic entities attaching themselves to the human inner consciousness, sowing chaos in the world as they take control. It is probably more relevant today than it was when he wrote it in 1967. The ‘mind parasites’ cannot be fought with conventional weapons; instead, new ways of expunging them need to be developed. Could the power of peak experience make us more resilient against the propagandists, manipulators and deceivers of this world? It’s an idea worth pursuing.

If you’re interested in knowing more about Colin Wilson’s life and philosophy, I can highly recommend Gary Lachman’s book Beyond the Robot.

Daniel Schmachtenberger’s video series The War on Sensemaking can be seen here.

And lastly, a film is currently in the works about Colin Wilson’s life and work. If you’d like to support it you can do so here. Here’s a short clip.

Being as i am commenting from our camping spot near the top of a mountain ridge via cell phone, i will break my comment up into pieces. Luckily, at the very top of the mountain, there is a cellphone tower and i am getting fabulous reception.

Speaking of peak experiences, Albert Hoffman the discoverer of LSD tells in a memoir of a peak experience he had in his youth. When I read that, I got the notion that perhaps LSD had chosen him to introduce it to us humans rather than him having discovered it.

Generally, our human centric perspective regards us as the discoverers of all things worth discovering. Native perspectives on the other hand sees useful things such as healing plantsas introducing themselves to us.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rinzai Zen while not necessarily advertising itself as a path to peak experiences does use stress to trigger breakthroughs away from ordinary cosciousness. The student has to confront the teacher with an answer to his koan for which he doesn’t have an answer, day after day until he finally snaps and enters a state where no answer is necessary.

LikeLike

Agree on the everything is ok with the cosmos notion. Had one of those experiences in my youth and various lesser versions of it over time. My day to day experience is probably no different than anyone else’s except maybe I worry a little less about the future than the average American and feel a little less moved to improve the world since no matter what we do it will be ok. This is not a philosophical stance but rather an experiencial or gnostic stance. Totally opposite of nihilism I think.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, absolutely. From my own experience of suffering from nihilistic despair, back in my teenage years, I can see that it’s really just a negation of the self being projected out onto a wider reality. It’s like saying “The pain within is so great that I’m going to destroy my inner self and bring everything else down with me”. Your gnostic state puts things in perspective and is strangely empowering as a result.

Re LSD – I am getting more and more convinced that these things are given to us by some higher intelligence. DNA was discovered in the same manner. Quite often, it seems, these breakthroughs tend to follow the discovery of new bodies in the solar system. Not always good … nuclear weapons were invented following the discovery of Pluto (or it may have been Uranus, I can’t quite remember). No idea why …

Enjoy your camping! I’d love to be up a mountain in a tent right now…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Jason,

Came across from the link you posted on ecosophia. I’m enjoying the posts and looking forward to see where you go with them.

Had a quick look at the Schmachtenberger video. Looks really interesting. I’ll watch in full when I get a chance.

I think, though, there’s a difference between the fight-flight response triggered by the amygdala and the appeals to emotion (esp. fear) which inevitably cause chronic stress and are really very unhealthy. I have, I think only once in my life, had a genuine amygdala-driven flight response. This was back when I was a teenager. Some friends and I were walking at night in suburban Melbourne returning to my friend’s house after eating dinner somewhere when three carloads of men pulled up suddenly and ran towards us. Imagine hearing screeching tyres then turning around to see a group of strangers running towards you with clearly violent intent. That was definitely an amygdala response because there was no time to evaluate the situation or feel emotion of any kind. We just started running instinctively. (Happy ending too. We got away. We later learned the guy thought we stole his car stereo. Must have been a good stereo).

Funnily enough, I would call that occasion a ‘peak experience’ in your language because that massive shot of adrenaline gets you focused very intensely on your surroundings. It’s not quite up there with facing death from a firing squad, but it’s closer to that than a night watching tv.

LikeLike

Hi Simon – thanks for stopping by. I understand your point. I can’t recall ever having a strong fight or flight response to anything, although I’m sure I must have at some point – possibly as a teenager trying to avoid the local bullies in the park. The extent that this is different to an appeal to emotion is the real crux, I suppose. With some people, although by no means all, I really do think they can be ‘triggered’ by seeing something on a screen in the same way that they would be ‘triggered’ by finding a giant spider sitting on their head. I’ve seen people act in completely irrational ways just by being presented with a news story, or even just an image. I can’t quite relate to this myself, but I’ve become convinced that it exists.

Glad to hear you got away from those men. I think you can instantly tell if someone means to harm you – you did good!

LikeLike

On propaganda: in the US, physical distance from the rest of the world makes it easier to feed the people bullshit because the majority never gets out much. Even of mexico, most americans don’t know much. The scary stories keep travelers at home. Immigrants are of course better informed but care little about propaganda. They know that america is where the money is and that is why they’re there. They work hard and know that their dollars are worth ten times more at home, so who cares if the Americans are ill informed. Everybody is happy.

To the propagadists, strife, chaos and fear keeps their product selling. I like the immigrant approach. Ignore the bullshit and pick up the money that falls on the floor.

LikeLike

I agree with that. You made me laugh with that. I’m not from the US but I know what you mean. It is maybe roughly the same with the UK’s relationship to, say, eastern europe. I imagine eastern europeans think “the brits are so well off, they all earn tons, even the poor”, but the thing is, the brits have to live there, they don’t have a “home” to go to where the pounds are worth ten times more.

Are you American or Mexican?

LikeLike

Dan, I am an American living in Mexico. My comment vastly simplifies the situation of course. You can game the income vs. Cost of living anywhere and amitious people often do, but my main thrust was to point out that people who travel can gather their own information and are less vulnerable to their own government’s propaganda.

LikeLike

Apologies, I’ve been away from the computer for a while doing various ‘urgent’ things before our cages are locked again. Maybe you’re right about Americans and propaganda. Saying that, most people ‘over here’ swallow it lock stock and barrel without too much persuasion, so maybe we are catching up.

Speaking of being ill-informed, I remember at the newspaper I used to work at in Denmark one day we had a new journalism intern from the US. He was very bright eyed and eager and so I gave him a few of the more fun tasks to do. One day a dedicated Tibetan man turned up at the office on a bicycle – he had cycled all the way over the Himalayas and through Russia to raise awareness of the Tibetan issue. Our young (well, probably about 24 years old) intern sat down to interview him and his first question was “So, what is this ‘Tibet’ thing then? Is it a brand or something?”

LikeLike